From an In-Depth Article by Drew Anderson, The Narwhal News, June 4, 2022

Mapping the growth of the toxic reservoirs shows just how far they’ve expanded since 1975, amid a surge in bitumen (tar) mining.

Picture downtown Toronto. All the condos, subways, roads, office towers and people. Now cover the whole thing with a toxic lake. Maybe you’ve never been there. Have you done the drive from Calgary into the Rockies? Imagine almost the entire 105-kilometre stretch from the city to Canmore as one continuous vista of oilsands tailing ponds.

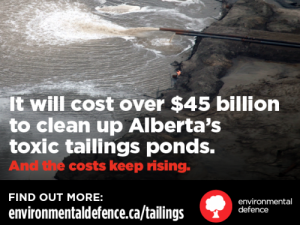

According to a new report titled “50 Years of Sprawling Tailings” from Environmental Defence and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, those are just two examples of how large the tailings ponds in northern Alberta have grown.

And despite new rules introduced in 2016 around managing tailings, the ponds have continued to grow, according to the report. This growth represents an increasing ecological and economic risk that will cost billions of dollars to clean up and could leave taxpayers footing the bill.

So what exactly does that look like on the ground? And what impact do tailings ponds have?

Here’s a bit of background ~ What are tailings ponds?

First thing to note, and it’s something the authors of the report stress right off the top: the ponds are anything but ponds as most people understand them.

“To be calling them ponds when tailings ponds actually are far larger than anything you would ever describe as a natural pond — it’s deception,” Gillian Chow-Fraser, co-author of the report and boreal program manager for the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, says.

“I don’t think it’s being very accountable to the level of destruction that’s happening in northern Alberta.”

One of the largest ponds, notes Chow-Fraser, is eight kilometres long. That’s almost as long as Alberta’s famed Sylvan Lake. Looking further afield, that will almost get you to the top of Mount Everest.

That said, the report uses the term pond to maintain consistency while expounding on the decidedly un-pond-like size of the waste reservoirs.

Inside those ponds is a toxic mix of byproducts from the mining of oilsands, including arsenic, naphthenic acids, mercury, lead and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons — all of which can impact ecosystems, wildlife and humans.

The ponds also emit air pollution that extends for kilometres.

The purpose of the ponds is to allow the byproducts of mining to separate from the water and settle at the bottom of the pond, a process that can take decades or more. Once those byproducts are settled, the pond can be drained and capped with soil to achieve some level of reclamation.

Why are Alberta oilsands tailings ponds still growing?

The tailings ponds have been growing for nearly 50 years, increasing in size by nearly 800 per cent in the late 1970s, before continuing to grow at varying rates, depending on factors such as global demand for oil and the state of the economy. Most recently, the size of the tailings ponds grew by over 50 per cent from 2010 to 2015, and then by just over 16 per cent from 2015 to 2020, according to the report.

There are now 30 active ponds in the region, the report also says.

The authors used satellite imagery going back to 1975 to measure the physical growth of the ponds — including the fluids and the related impacts such as berms and areas where dry tailings are stored — but not the volume of tailings they hold.

For that they relied on Alberta Energy Regulator reports (more on that shortly).

Aliénor Rougeot, co-author and climate and energy program manager for Environmental Defence, says they included things like berms and beaches created by the ponds — where you would not want to sunbathe — because all of it impacts the surrounding area.

“That’s the peatlands and boreal forest that were taken away, or that’s the area that the Indigenous communities can no longer have traditional practices on,” she says.

In total, the report says the footprint is 300 square kilometres, big enough to more than twice cover the city of Vancouver or a large chunk of Toronto.

“I live in downtown Toronto, and so I think I know what large means, I think I know what human activity taking over nature looks like,” Rougeot says. “And yet when I saw the scale when I saw those maps, especially the layovers of cities. I mean, that was just baffling to me.”

Ponds increase as new expansions or new mines are approved and the existing ponds fail to shrink.

The report did not trace the rise in the volume of the ponds, but that has also increased over the years, and the report notes current levels are 1.4 trillion litres of tailings based on Alberta Energy Regulator figures.

……. much more in the Article and the Report!