Study indicates gas drilling can impact rivers, streams & wetlands

From an Article by Elizabeth Krapits, Citizens Voice News, November 16, 2015

Depending on where and how it’s done, natural gas drilling does have the potential to impact Pennsylvania’s waterways, an independent study reveals.

Kenneth M. Klemow, professor of biology and environmental science and director of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research at Wilkes University, was one of the contributors to a new study examining how natural gas development affects surface water, such as creeks, streams and rivers.

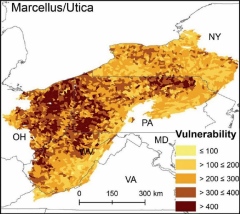

In their paper, “Stream Vulnerability to Widespread and Emergent Stressors: A Focus on Unconventional Oil and Gas,” Klemow and five colleagues look at how vulnerable the bodies of water are in the six main shale plays across the U.S., including the Marcellus Shale.

“What we’ve developed is a predictive model,” Klemow said. “We have not proven anything about whether shale gas development is affecting streams or not.”

Watersheds are areas from which all the water beneath it or on it drains into the same place, whether creek, stream, river or lake. Surface water is used for drinking water, recreation, and feeds into fisheries, Klemow said.

Despite the importance of surface water and the fact that natural gas-related activity is increasing, there were no studies on whether the activity might contaminate streams. “That was the impetus, realizing there was a gap in the knowledge,” Klemow said.

In addition to Entrekin, other principals on the paper were Kelly O. Maloney of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Northern Appalachian Research Laboratory in Wellsboro, Tioga County; Katherine E. Kapo of Waterborne Environmental Inc. in Leesburg, Virginia; Annika W. Walters of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Wyoming in Laramie; and Michelle A. Evans-White of the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville.

The scientists pooled their data; Klemow said Wilkes supplied “quite a bit” collected by the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research.

“It was an exercise in going out online and getting whatever data we could about different watershed characteristics,” Klemow said. “For every watershed within the shale plays, we got a whole bunch of data: slopes, soils, type of vegetation, then things like land use.”

The bulk of the work involved using online databases and computer modeling with a geographic information system, or GIS. Klemow said Entrekin and Maloney, the lead authors, were the “GIS gurus,” so they did the bulk of the analysis in terms of crunching the numbers. The other authors provided interpretation and commentary.

What they found

In addition to the Marcellus, the researchers studied the Bakken shale, an oil-rich shale primarily being developed in North Dakota; the Fayetteville shale, a natural-gas shale in Arkansas; the Hilliard and Mowry shales in Wyoming and the oil- and gas-rich Barnett shale in Texas.

The study notes that “The fast pace and wide extent of unconventional oil and natural gas development raises concerns about its ecological effects.”

The researchers looked at the sensitivity of watersheds in the shale regions to impacts, and discovered that, of the six different plays, the Marcellus turned out to have the lowest, Klemow said. The others are in the central or southern part of the country where they don’t get as much rainfall. What makes the Marcellus region more resistant to impact is the fact that it gets a lot more rain than the other shales. But the Marcellus does have steep slopes and fairly loose soils and sediment.

The researchers next looked at exposure, a measure of the degree to which the watersheds could be affected by proximity to potential sources of pollution such as urbanized areas, farm land, coal mining or gas drilling — especially taking into account things like well pad density and access roads.

They found that despite its low sensitivity to impact, the Marcellus Shale has high exposure where drilling is heaviest, in northeastern and western Pennsylvania, Klemow said. A lot of shale gas development has already taken place, as well as many years of agriculture and mining. In the western part of the state there is also conventional oil and gas drilling, he said.

The researchers then took the sensitivity of each shale play, multiplied it by exposure, and came up with its vulnerability score, which is the amount of risk a particular watershed has.

Klemow said Northeastern Pennsylvania has a lot of watersheds classified as being highly vulnerable, mainly because they have high exposure rates.

Where the drilling is and how close it is to streams makes a difference. If you have a gas well that’s three miles away from the nearest stream, the chance of contamination is pretty low, Klemow said. But if it’s 300 feet from a stream, it’s going to be a lot higher. In other words, as Klemow puts it, it’s a highway with a lot of traffic on it, which makes it

“Wouldn’t pipelines raise the exposure level? The answer is, absolutely yes,” Klemow said. “But we couldn’t get any good pipeline data.”

What he hopes the study will lead to is the natural gas industry using best practices — such as being careful crossing streams — and having good regulations in place. It’s like if every motorist on the road drives safely, and there is good police enforcement, there won’t be as many accidents.

“One take-home is, this is now a predictive tool that hopefully regulatory agencies will be interested in, and hopefully the industry will be interested in this,” Klemow said of the study.

See also: www.FrackCheckWV.net

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

John Stolz warns of danger when past, present drilling practices collide

Dr. John Stolz: Microbiologist, independent expert on how fracking can affect well water and director of Duquesne University’s Center for Environmental Research and Education.

Stolz worries that drillers and regulators pay too little attention to “legacy issues” — the presence of old coal mines and conventional gas wells drilled before the fracking arrived on the scene. He believes contaminants associated with mine drainage that are found in some water wells are caused by new “conduits” in the rock created by fracking. He says old mines in places like the Deer Lakes Park area might well cause problems if drilling happens. “The damage,” he says, “is gonna start popping up in places it’s never popped up before.”

http://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/john-stolz-warns-of-danger-when-past-present-drilling-practices-collide/Content?oid=1752840#.Vmwvj_dFHY8.gmail