From an Article by Phil McKenna, Inside Climate News, Oct 11, 2020

For natural gas pipeline developers hunting for a good deal on a 100-mile section of steel pipe, a recent advertisement claimed to have just what they are looking for.

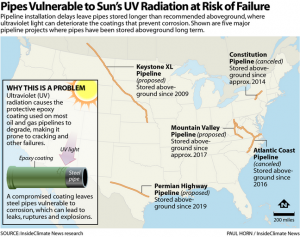

Following the cancelation of the proposed Constitution natural gas pipeline in Pennsylvania and New York, a private equity firm recently offered a “massive inventory” of never-used, “top-quality” coated steel pipe.

What the company didn’t mention is that the pipe may have sat, exposed to the elements, for more than a year, a period of time that exceeds the pipe coating manufacturers’ recommendation for aboveground storage, which could make the pipe prone to failure.

Long term, aboveground pipe storage has become commonplace as pipeline developers routinely begin construction activity on pipeline projects before obtaining all necessary permits and as legal challenges add lengthy delays.

Whether canceled or stalled, overdue oil and gas pipelines across the country may face a little-known problem that raises new safety concerns and could add additional costs and delays.

Fusion bonded epoxy, the often turquoise-green protective coating covering sections of steel pipe in storage yards from North Dakota to North Carolina, may have degraded to the point that it is no longer effective. The coatings degrade when exposed to ultraviolet radiation from the sun while the pipes they cover sit above ground for years.

The compromised coatings leave the underlying pipes more prone to corrosion and failures that could result in leaks, catastrophic spills or explosions. Degraded coatings were implicated in an oil spill from a failed pipeline near Santa Barbara, California in 2015. Toxic compounds may also be released as the coating breaks down, raising concerns that the pipes could pose a health threat to those who live near the vast storage yards holding them.

“There are pipelines being built all over the place and it doesn’t seem like anyone is keeping close track of what the status is of the coatings,” said Amy Mall, a senior advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “There are a lot of unknowns here and yet we’re relying on the coating to protect landscapes and communities from massive explosions.”

‘No Longer Acceptable’

The National Association of Pipe Coating Applicators, an industry group, states that “above ground storage of coated pipe in excess of 6 months without additional ultraviolet protection is not recommended.”

However, photographs and satellite images suggest pipe sections for the Constitution Pipeline may have been stored aboveground without ultraviolet protection for more than a year before they were covered in “whitewash”—common household paint—that shields their coatings from the sun.

Pipeline safety experts question whether the pipe is still safe for use as part of a natural gas transmission pipeline. “If they are going to sell it and use it for line pipe for natural gas, then they need to go back and do extensive testing on it before they put it in,” said Richard Norsworthy, an industry consultant for pipeline coatings and corrosion control.

Sections for the long-delayed Keystone XL Pipeline, which would carry tar sands crude oil from Hardisty, Alberta to Steele City, Nebraska, may be in even worse condition. The pipes have been stored outside with only partial whitewash cover for nearly a decade.

TC Energy, which owns the pipes, inspected a small sample of them in 2018 and published what they found earlier this year in Corrosion Management, an industry journal. Environmental advocates say the findings are cause for concern. Company engineers analyzed 12 sections of pipe for the proposed pipeline that were stockpiled in Little Rock, Arkansas and were exposed to sunlight for up to 9 years.

The 80-foot pipe sections were coated with acrylic, water-based whitewash. However, several feet at the ends of each pipe were not covered to avoid hiding identification markings stenciled onto the pipe, the report said. It concluded that the green protective coatings on areas that were not whitewashed “completely failed to retain their original properties and attributes.”

Those properties and attributes include things like coating thickness, flexibility, absorption capacity and the ability to adhere to the underlying steel pipe. Their purpose is simple; they keep the underlying steel from rusting.

If even a portion of the coating wears away, cracks, allows water to permeate it, or fails to stick to the pipe, water contacting the pipe’s bare steel can cause it to rust. If enough rust forms on the pipe the steel can thin to the point that it forms a hole or rupture, spilling oil or leaking gas that can explode.

“You don’t have to be a specialist to read that and see that it’s saying that all those ends of those pipes that weren’t coated with whitewash were total failures,” Bill Kitchen, an environmental advocate in Johnstown, New York, said of the Corrosion Management study.

Portions of the pipe that were covered in whitewash had thicker protective coatings that adhered more closely to the underlying steel, yet failed another key test, according to the study. The pipe coating’s flexibility, which prevents the coating from cracking, was “adversely affected to the point where the coating was no longer acceptable,” it said.

Coating flexibility is crucial for pipes as they can be lifted and set down more than a dozen times as they are moved before being buried underground.

“When they pick that pipe up, no matter how they pick that pipe up, it’s going to flex,” said Norsworthy. “And when it flexes, it cracks,” he said of degraded pipe coating that would not pass flexibility tests.

Coating failures can lead to pipeline failures, as was the case in May 2015 when 123,000 gallons of crude oil spilled near Santa Barbara after a steel pipe ruptured.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), the federal agency that regulates oil and gas pipelines, concluded the spill was caused by “external corrosion that thinned the pipe wall to a level where it ruptured suddenly.” The agency found that “the condition of the pipeline’s coating and insulation system fostered an environment that led to the external corrosion,” although, in this case, the coating hadn’t been degraded by exposure to sunlight.

Significant failures in pipelines transporting gas, oil and other hazardous liquids are increasing, with one fifth of all failures due to corrosion, according to a recent assessment of government data by the Pipeline Safety Trust, a watchdog group.

In June 2019, PHMSA issued a notice of probable violation to TC Oil Operations, a subsidiary of TC Energy, after realizing a related safety concern involving a pipeline that is already in operation. The company used fusion bonded epoxy, the same coating that should not be stored exposed to ultraviolet light from the sun for more than six months, on multiple, permanently above ground sections of the original Keystone pipeline, which was completed in 2010.

The company received an order in February giving it six months to “correct deficiencies in coating material” and provide a record of the location and date that an “appropriate coating” was applied. TC Energy complied with the order and the case is now closed, according to a letter PHMSA sent to the company on Sept. 29. PHMSA would not say how the problem was remediated or what additional coating was applied.

#############################

The March for Science champions robustly funded and publicly communicated science as a pillar of human freedom and prosperity. Advocating for Science not Silence!