From an Article by Kristina Marusic, Environmental Health News, May 29, 2020

A new study has uncovered a link between fracking chemicals in farm water and a rare birth defect in horses—which researchers say could serve as a warning about fracking and human infant health. The implications for human health are “worrisome,” say researchers.

The study, published this month in the journal Science of the Total Environment, complements a growing body of research linking fracking to numerous human health effects, including preterm births and high-risk pregnancies. This is believed to be the first study to find fracking chemicals in farm water linked to birth defects in farm animals.

In 2014, veterinarians at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals in Ithaca, New York, realized that they’d diagnosed five out of 10 foals born on one farm in Pennsylvania with the same rare birth defect. The birth defect, dysphagia, involves difficulty swallowing caused by abnormalities in the throat. Dysphagia causes nursing foals to inhale milk instead of swallowing it, which often results in pneumonia if milk gets into their lungs.

The birth defect is so rare that the rate among the general population isn’t known, but one paper on health outcomes in horses from a large university veterinary neonatal intensive care unit documented just five cases of dysphagia out of 1065 hospitalized foals—a rate of less than 0.5 percent.

The owner of the Pennsylvania farm the horses came from also owned a farm in New York. Both farms used the same commercial horse feed and sourced hay from the same place—but none of the horses born on the New York farm ever had dysphagia. Additionally, several mares that lived on the Pennsylvania farm for the first half of their gestation had healthy foals after being moved to the New York farm mid-pregnancy, while several mares who started out in New York and were moved to Pennsylvania mid-pregnancy had dysphagic foals.

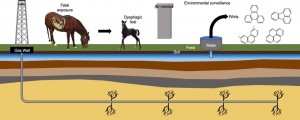

The only difference the farmer identified was that in Pennsylvania, there were 28 fracking wells within seven miles of the farm—two of which were within 1,500 feet of the property’s two water wells. There were no fracking wells near the New York farm. The state banned the practice in 2015 following a seven-year review of its health and environmental impacts, during which time there was a moratorium on it.

“We realized this was a really rich study opportunity,” Mullen said, “so we decided to look more closely to see if environmental factors were associated with the dysphagia cluster.”

Over the next two years, Mullen and colleagues analyzed samples of feed, soil, air, and water, and samples of blood and tissue samples from mares and foals at both farms. During that time, 65 foals were born, 17 of which were dysphagic—all of them from the Pennsylvania farm.

They didn’t find significant differences in the feed, soil, air, or blood and tissue samples from the two farms. But they did find a significant difference in the water: There were higher levels of four kinds of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—chemicals commonly used in fracking—in the water at the Pennsylvania farm that weren’t seen in water at the New York farm. Those chemicals included fluoranthene, pyrene, 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene, and triphenylene, all of which have been linked to health problems in humans and animals.

Following that discovery, the farmer installed a water filtration system, which brought the levels of PAHs in the water on the Pennsylvania farm down to levels comparable to those seen at the New York farm. After that, they saw a marked decrease in the birth of dysphagic foals: In 2014, 26 percent of all of the farmer’s foals had been born dysphagic; in 2015, 41 percent were dysphagic; and in 2016, after the installation of the filtration system, the rate fell to 13 percent.

The researchers believe the reduction in PAHs in the water, along with a reduction in the amount of time the mares were spending on the Pennsylvania farm during their pregnancy, led to the corresponding reduction in birth defects in the horses—though Mullen added that more research is needed to evaluate the toxicity of those chemicals at the levels they observed.

“I think it’s a bit soon to say that all farms should have filtration systems installed for their wells,” she said, “but this study does provide at least preliminary evidence that well water in places with unconventional natural gas development can see increased levels of PAHs.”

A spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Farm Bureau told EHN the organization hasn’t yet had time to fully review the study, but noted that “animal health is among the top priorities for Pennsylvania farmers, and scientific research plays a critical role in helping farmers develop practices to best care for their animals and understand factors that may affect their animals’ health.”

Mullen said she believes the study adds to the growing body of literature linking fracking to problems with human fetal development.

“Horses are often sentinels of health risks to humans,” she said. “Right now we can only speculate that what we saw in these foals also translates to human health risk, but the implications are certainly worrisome.”

###########################

See also: We’re just starting to learn how fracking harms wildlife, Tara Lohan, The Revelator, October 3, 2019

The cumulative footprint of a single new well can be as large as 30 acres. In places where hundreds or thousands of wells spring up across a landscape, it’s easy to imagine the toll on wildlife — and even cases with ecosystem-wide implications.

“Studies show that there are multiple pathways to wildlife being harmed,” says ecologist Sandra Steingraber, a distinguished scholar in residence at Ithaca College who has worked for a decade compiling research on the health effects of fracking. “Biodiversity is a determinant of public health — without these wild animals doing ecosystem services for us, we can’t survive.”