Smoke From California Wildfires Is Reaching the East Coast

From an Article by Jennifer Calfas, Time Magazine, August 10, 2018

Smoke billowing from the destructive fires burning through California this summer has spread far beyond the Golden State — reaching the East Coast.

The National Weather Service says smoke from the raging fires out West has impacted cities thousands of miles away — and the atmosphere above them. Residents in states like Missouri, Ohio, Mississippi, Virginia and even New York and Massachusetts can see the smoke manifest itself through grey skies and vibrant sunsets, the National Weather Service says. And those in fewer states throughout the Midwest, South and East Coast are breathing in air that has been impacted by the smoke as well.

But how exactly does smoke travel this far? Andy Edman, chief of the science technology infusion division at the National Weather Service, says small particles of smoke that come from the fires can stay in the air and move through the Earth’s atmosphere — all the way to the East Coast. The smoke sits more than a mile above the Earth’s surface, but can move down through strong winds called jet streams and have an impact on air quality.

“Where the smoke is in the atmosphere will make a difference on the impact a human being will receive,” Edman says. For example, with the smoke far from the Earth’s surface, Edman says, “if you’re in D.C. or New York, if you walk outside, it will all seem sunny but if you look up at the sky, it will be grey.”

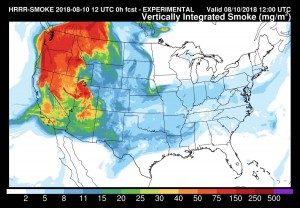

The National Weather Service has two relevant maps that explores the issue. One below shows the path of “vertically integrated smoke” — that is, the smoke that sits far above Earth’s surface in the atmosphere and impacts the sky you see above you.

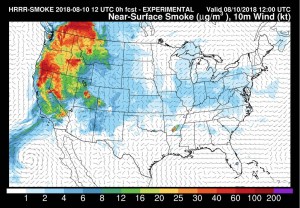

The other map below shows the movement of “near-surface smoke,” which, as its name suggests, shows the levels of smoke near the Earth’s surface that have an impact on air quality.

Particles from smoke near the Earth’s surface can cause a range of health issues, including respiratory problems, and aggravate lung and heart issues. Officials advise people living in areas impacted by the smoke to take safety measures by staying in doors and running air conditioning units.

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station captured images of smoke from these fires from space earlier this week, showing the smoke’s eastward shift and massive reach. Edman, of the National Weather Service, says not all fires can create this long-ranging stream of smoke, but the cumulation of fire after fire after fire in the state has made it possible this time around.

“When you have that many fires, it’s not uncommon for that smoke to go fairly long ways downstream,” Edman says.

Smoke particles from fires in California traveled far last year, too, when satellite images from NASA showed the smoke traveling over to the East Coast. Thanks to new technology, Edman says, the National Weather Service has been better able to track the movement of smoke across the U.S. from fires based in California, capturing it in visualizations and maps for just a few years now.

Meanwhile, in California, 15 active wildfires are burning throughout the state as a destructive and record-breaking fire season rages on. The Mendocino Complex fire just north of San Francisco became the largest fire in state history earlier this week, scorching through 307,447 acres and destroying 119 homes as of Friday morning. Other fires have blazed through tens of thousands of acres across the state. That includes the 181,000-acre Carr fire, which has destroyed more than 1,000 homes in Redding, Calif., and taken at least eight lives. The Ferguson fire blazing near Yosemite National Park prompted park officials to close popular sections of itfor the first time in 20 years (and during peak season), and the Holy fire down in Orange County forced tens of thousands of residents to evacuate their homes.

Fueled by extremely dry vegetation, record-setting temperatures and the aftermath of a years-long drought, fire seasons in California have grown more intense in recent years and death and destruction has become the norm.

########################

See also: “Colorado wildfire update: Smoke and haze continue to cloak the state.” By Anna Staver, August 20, 2018

Smoke and haze will be visible throughout Colorado on Monday as firefighters across the west continue to work to put out dozens of wildfires. It’s been a difficult season for wildland firefighters around the county. In Colorado, five fires that started this season grew large enough to make the state’s top 20 list. Presently, 12 wildfires are burning in the Centennial State, but most are at 90 percent containment. Here’s a roundup of major wildfires around Colorado.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

What’s a smokestorm? A meteorologist explains

From an Article by Kate Yoderon, The Grist, August 23, 2018

As wildfire smoke descended on Seattle this week, the sun turned an apocalyptic shade of red and the city breathed in some of the unhealthiest air in the world. A new word to describe this phenomenon graced the headlines: “smokestorm.”

The person who coined the term is Cliff Mass, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington and revered Seattle meteorologist. “A Smokestorm is Imminent,” read the title of his blog post last Saturday, in which he projected the dangerously smoky days ahead for northwest Washington state.

“You have heard of rainstorms, snowstorms, and windstorms,” Mass wrote. “It is time to create another one: the smokestorm.”

I called up Mass on Wednesday — the day before a drizzle came in and the smoke began to dissipate — to hear the story behind the term and what he thinks we can do to prevent future smokestorms.

He came up the word to help prepare people for the hazardous air conditions. “I just wanted to give people a heads up, and something dramatic probably was more effective than ‘air quality alert,’” Mass tells me.

Mass defines a “smokestorm” as “a sudden onset of high concentrations of smoke that are large enough to affect daily life.”

Like other types of storms, a smokestorm disrupts normal operations. In Seattle this week, flights were delayed. The tourism industry took a hit. State health officials even started warning people not to vacuum.

“This was the worst [smoke] event we had in 20 years,” Mass tells me. “But one thing you can keep in mind is that people are not old enough to remember what it was like in the early 20th century and before.”

Mass says that Seattle was historically a “very smoky place.” He points to an example: In 1895, when Mark Twain visited Olympia, the capital of Washington, the city’s reception committee apologized to him for the dense smoke from wildfires that clouded picturesque views of the Olympic Mountains.

Wildfires and smoke were part of life, but they weren’t like the giant blazes or smokestorms we see today. In additional to naturally occuring blazes, indigenous groups in the area would start low-intensity burns for hunting and clearing the land to gather food — a practice that stands in stark contrast with the aggressive fire suppression practiced during the last hundred-plus years.

The forests are now overgrown and “completely unlike what they were like 150 years ago,” Mass says, “and they tend to burn these large fires which sometimes we just can’t stop.”

There’s considerable agreement among scientists that climate change is making drought and heat — and consequently, wildfires — worse. But it’s not the only factor at play here. Mass calls the climate change explanation for wildfires a “simplistic narrative,” though he acknowledges the danger it poses. (Recently, some in the climate community have criticized Mass’ approach to climate.*) “Climate change is going to get more and more serious as time goes on, so you gotta worry about that,” he told me.

In addition to overgrown forests, Mass places some responsibility on the spread of invasive grasses — which he referred to as “grassoline” — that burn more readily than Washington’s native grasses.

So how do we put a stop to gigantic fires, and thus smokestorms, in the West? Mass says the key is proper forest management: Clearing out excess fuel and doing low-level prescribed burns.

“It would cost billions of dollars to do,” Mass says, “but we’re gonna pay for it anyway. You might as well do it smart and take care of it.”

Source: https://grist.org/article/whats-a-smokestorm-a-meteorologist-explains/