WV gas industry sues landowners to “legally” perform forced-pooling of mineral rights

From an Article by Andrew Brown, Charleston Gazette, June 21, 2015

West Union, WV — When Lorena Krafft received the court summons in 2013, she didn’t quite understand what was happening. Months before, she had received a letter and a draft lease from Antero Resources asking her to sign over a portion of minerals she owns in Harrison County so the company could drill. She ignored that letter and the string of calls that followed. She told the company to consult with her attorney.

It wasn’t that Krafft, a resident of Ohio, was opposed to drilling. She had been willing to lease the 15 pieces of property she inherited from her mother in Doddridge and Harrison counties. The problem was that her interactions with Antero had soured because of disagreements over the location of a gas-compressor station and the cutting of trees on land she owns in Doddridge.

She wanted those issues resolved before she would sign a lease with the company. Instead of bringing the company to the negotiation table, though, Krafft’s refusal to sign prompted Antero to file a lawsuit in Harrison County Circuit Court seeking to end her ownership in the tract of minerals.

Without Krafft’s signature on a lease, the entire Marcellus Shale well that would be drilled through nearly 14 properties could be put on hold, delaying profits for Antero and the other property owners, who already had signed over their mineral rights.

Krafft’s case is just one example of how the oil and gas industry has turned to West Virginia’s court system in the absence of a pooling law to force mineral owners to either sign leases or sell their property. In county courthouses throughout the north-central part of the state, gas companies have filed what are known as partition lawsuits, seeking court-ordered buyouts of partial mineral owners who have yet to sign a lease.

In Doddridge and Harrison counties alone, Antero, one of the region’s largest gas producers, has filed nearly two-dozen lawsuits over the past two years. Lawyers who have worked on similar cases in the state say the lawsuits also have been used by other companies, like EQT Corp., in the state’s other Marcellus gas-producing counties.

For the companies, the lawsuits are a necessary part of their effort to clean up the state’s fragmented mineral acreage, which often is split between dozens of shared owners, the result of property being passed down through generations, sometimes unknowingly.

For the people who are sued, though, the litigation often is seen as an unfair process in which they are either compelled to sign a lease or watch as their property is sold to a gas company for whatever price the court determines is fair — often less than what can be made from the minerals once they are drilled.

Two years after the lawsuit was filed, Krafft continues to fight Antero in court, an effort that has cost her a significant amount of money and shaken her confidence in the court system. “We’re tired of it. We are tired of the expense. We’re disillusioned with our legal system because the cost is outrageous. From attorney fees to court fees, the amount of money that is involved is way beyond our imagination,” she said. “You get the feeling they are just waiting for us to run out of money, to get tired and give up. But what do you do? You have this much money invested already.”

In lieu of ‘forced pooling’

The use of the lawsuits coincides with several years of failed attempts by the industry to push a forced-pooling bill through the West Virginia Legislature — the most recent defeat coming three months ago, when a large number of Democrats and the right wing of the state’s Republican party united to force a last-minute tie on the controversial bill.

A pooling bill would allow companies to group dozens of mineral tracts into organized rectangular areas, sign up at least 80 percent of the owners in that space and petition the West Virginia Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to force the remaining people to sign a lease.

If passed, the law would have ensured that drilling in West Virginia was as efficient as possible, reducing the amount of time and number of wells needed to get the gas out of the ground. Opponents of the law balked at the sections of the bill that required unwilling owners to sign a lease with gas companies. So, instead, gas companies have relied on the tools they do have at their disposal — namely partition lawsuits — to buyout or lease portions of shared minerals. The costly litigation can often take over a year to resolve, but industry officials say that, in the absence of forced pooling, the lawsuits are the only means available to open up mineral acreage for drilling.

In many ways, the lawsuits achieve the same goals that pooling would, but on a case-by-case basis in the county courts. One of the few differences is that the lawsuits can’t be filed against people who own 100 percent of their minerals, while forced pooling could.

“It is an indirect way to achieve what pooling would do,” said Jay Leon, a lawyer from Morgantown who has represented mineral owners in partition lawsuits. “The point is that it is a blunt instrument to get the property into production.”

Kevin Ellis, president of the West Virginia Oil & Natural Gas Association, said the need to remove the holdout owners — some of whom live in other states — is the only way to ensure that the cooperating property owners can profit from the minerals.

“It doesn’t make sense that litigation is the only way that you can get 100 percent development,” Ellis said, adding that the industry would rather use pooling, which he said would be a quicker and fairer process.

In West Virginia, all people with shares in a co-owned piece of property need to sign leases before a company can drill and hydraulically fracture a well. That can make it difficult for companies to secure those minerals.

While a gas company needs partial ownership in a tract of minerals to file a partition lawsuit, the development of those minerals has almost been guaranteed once it does.

In every case reviewed by the Gazette-Mail, Antero began by having one of the already-leased mineral owners sign a small portion of the property over to the company. Without that ownership — usually about 1 acre — the company can’t file the lawsuit. Lisa Ford, an attorney from Clarksburg, said the practice is an example of companies acquiring a “minuscule” interest and asserting what she believes is a perceived right to file a lawsuit. “While sitting on inventories of hundreds of thousands of acres, companies allege that individuals who ask for a square deal are refusing to cooperate in development,” she said.

Once a property transfer is finalized, there is very little the holdout owners can do, besides sign a lease or accept whatever price the court decides the minerals are worth. Even if the unwilling owners make up more than 48 or 50 percent of the ownership in a tract of minerals, court records suggest the companies have the upper hand.

Of the 16 Antero lawsuits reviewed from Doddridge County, at least 10 were dismissed after holdout mineral owners relented and signed leases. “It’s like any other type of negotiation; it comes down to leverage,” said Leon, who is representing Krafft in her lawsuit against Antero.

In cases where the court does determine a price for the minerals, court records show that the price is usually set around $2,500 per acre, and that the valuation often is based on evidence presented by the gas companies. Ellis, who also is an employee of Antero, said those numbers are based on the prices paid for other minerals in the immediate area, which court records show is normally previous purchases made by the same companies. “It’s no different than the sale of a house,” Ellis said. “You base it on what’s comparable in the area.”

Dave McMahon, a Charleston lawyer who represents mineral owners in the state, said that when clients have approached him in the past and asked how to handle a partition lawsuit, he told them to negotiate for the best lease terms they can get and sign with the company. McMahon, who is a founder of the West Virginia Surface Owners’ Rights Organization, said it’s often not worth fighting the company and losing out on the money that can be made from gas royalties.

For any of the owners, the decision between selling out or leasing can be difficult, but for people who object to drilling for conscientious reasons, like environmental or human-health concerns, the choice can be particularly hard to swallow.

‘A tangled mass of weeds’

In West Virginia, partition lawsuits — meant to resolve disputes between co-owners of land and minerals — are well established in the legal system. They’re relics from English law, passed down from when the state was still part of Virginia. But while the law has been used for decades to settle land disputes and open up minerals for mining and drilling, some people involved in the lawsuits have recently questioned if the right to partition gas minerals is guaranteed and whether the gas companies’ particular use of the law is actually legal or not.

In September, Judge Timothy Sweeney issued a decision in a Pleasants County Circuit Court case — Elder v. Diehl — that challenged what has been an almost guaranteed right to force the sale of other people’s minerals. “Partition is not an absolute and unqualified right,” Sweeney wrote in the decision, which denied a private mineral owner’s request to sell off a co-owner’s portion of the property.

Sweeney, who has presided over numerous partition lawsuits in the past couple years, also called on the West Virginia Supreme Court to review the case. He wrote that the use of the law to partition minerals is like fitting a “round peg into a square hole.”

“The current state of partition law in West Virginia is a tangled mass of weeds,” Sweeney wrote. “The court finds this to be especially true with regard to oil and gas minerals.”

Sweeney’s opinion immediately caught the attention of law firms that represent the gas companies in the state. They quickly posted messages that warned of the possible implications the decision could have for the industry. They argued that it was evidence of the need to convince the Legislature to pass a forced-pooling bill.

Still, industry officials remain confident in their legal right to file the lawsuits. “The Supreme Court has already ruled on the validity of the partition statutes,” Ellis said. “I am aware of the case in Pleasants County. He has an opinion. It’s out there. To my knowledge, the partition statute is applicable to oil and gas, the same as it is to the utilization of the surface.”

But Judge Sweeney is not the only person who has reservations about the recent number of partition lawsuits that have been filed in county courts. Numerous lawyers who have represented mineral owners, including Attorneys Leon and Ford, argue that the way the companies file the lawsuits might not be exactly legal, according to their reading of the law.

In every case reviewed by the Gazette-Mail, the companies named as defendants only the owners who wouldn’t sign leases, which Ford said was a type of “procedural Hail Mary.” Leon said that practice might go against the basic purpose of the partition law, which is meant to leave the entire property in the hands of a single owner. “That’s not what the statute was meant to do, in my humble opinion,” Attorney Leon said.

In Krafft’s case, several of her relatives who signed leases and shared ownership in her tract of minerals were named as plaintiffs against her. She said they were never consulted by the company about the lawsuit and wouldn’t have consented to their names being used in a case that was seeking to force the sale of her property.

If the companies were forced to name all owners as defendants, the attorneys said, even the people who signed leases with the company would be forced to sell their minerals, making it more difficult for companies to get people to sign over an acre of the property to begin with.

But without a case being appealed to the state Supreme Court, Attorney Jay Leon said, the attorneys, judges, companies and property owners involved in the lawsuits are left to operate in an unclear legal environment. “For the most part, these are 100-year-old concepts that are being applied in a unique environment,” he said. “When these laws were created, they didn’t foresee horizontal drilling. The law is playing catch up a little bit. It’s a new wrinkle to an old problem.”

Attorney Lisa Ford maintains that the lawsuits are illegal and violate the rights of property owners. “This suspect partition practice is causing great harm to West Virginians. Companies are taking mineral interests without affording West Virginia mineral owners their constitutionally guaranteed due process of law,” she said. “In my opinion, there are holes in the industry’s scheme to take mineral properties with our partition statute that are big enough to drive a water truck through.”

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Gazette Plus (6/21/15) The Rest of the Story ……

‘I didn’t want to participate’

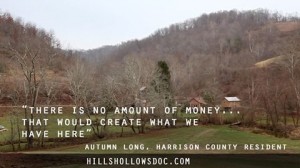

Lunell Haught, a resident of Spokane, Washington, and Barbara Wayne, who lives in Virginia, had decided that they didn’t want to take part in gas drilling under other people’s land. They had inherited shares of minerals in West Virginia, and both have relatives in the state, but neither wanted to profit from the controversial practice of drilling and hydraulically fracturing a well.

“I didn’t want to participate in people’s homes being impacted by forces that were not in their control,” Haught said.

In recent years, though, both women found that they didn’t have a choice. After ignoring multiple requests from gas companies asking them to sign a lease, the women were sued in separate partition lawsuits. They couldn’t believe state law could allow the companies to force them to sell the minerals.

“I was amazed to get that letter, but then again, this is West Virginia,” said Wayne, who grew up in the state.

At first, each woman considered fighting the lawsuits in court, but after seeking legal advice, each realized that cause looked hopeless. So, in acts of defiance, Haught donated her minerals to the surface owners’ rights association, in the hope of helping other property owners, and Wayne signed a negotiated lease and donated all of the money to an environmental organization focused on banning hydraulic fracturing.

Industry officials say holdouts like Haught and Wayne stop other mineral owners from profiting from drilling and inhibit state and local governments from making as much tax revenue as possible from the Marcellus Shale that underlies a large portion of the state.

Haught doesn’t begrudge anybody from making money from signing a lease, especially if it’s needed to make a house payment or to pay for groceries for their family, but she said it’s hard to understand how a company can buy a small percentage of the minerals and force anyone who won’t sign a lease off the property.

“If you let a camel put his nose in a tent,” she said, “pretty soon, he will be living there.”